|

| My pochade box with the Reilly's outdoor palette. |

Reilly created a landscape palette for his students that is well thought out and allows for quick access to important colors. A derivative of his Universal Palette, it emphasizes value while facilitating hue and chroma changes much like his figure palette.

Arranging the Palette

The first row are the controls values, made from titanium white and lamp black. Lamp black is much cooler in hue than ivory, and works to influence the shadow colors with a bluish tint.

The second row are the locals. They can be composed of cadmium lemon (at value 9), cadmium yellow light, cadmium yellow, cadmium yellow medium, cadmium yellow orange, cadmium orange, cadmium red light, cadmium red medium, cadmium red dark and alizarin crimson. It is not necessary to have all of these colors, as long as you have a string of various hues at different values. Other locals that come from the tube at value 1, like burnt and raw umber, can be added as well wherever they fit on your palette conveniently, but try to keep them lined up with the proper value.

In the chart below, a string of sky values are on the palette in quarter value increments from value 8 to value 9.5. My short-hand version of the palette above simply has sky values 8 and 9.5.

A string of green values for the foliage is created by using a formula given below.

I have used this palette for field studies several times this summer with great success in establishing values consistent with outdoor light, and in capturing the warm color of the light and cool color of the shadow. The palette was laid out prior to going outside, so it saves precious time on location, and like the figure palette, offers the convenience of having colors on hand that only require minor adjustments in hue and chroma to achieve the desired results. Another palette of convenience!

|

| 9"x12" field study #1 © John Ennis 2011 |

|

| 9"x12" field study #2 © John Ennis 2011 |

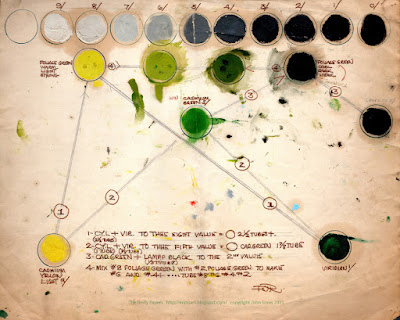

Mixing the Foliage Colors

This illustrated chart offers a visual guide in mixing and tubing the colors. We are creating a string of greens that are at one end yellow green, light in value, strong in chroma, an at the other end blue-green, dark in value, weak in chroma.

Begin with cadmium yellow light and mix it with viridian to the 8th value (#8 Foliage). Mix cadmium yellow light with viridian again to create a value 5 green (cadmium green). This color is then mixed with lamp black to create #2 Foliage. Mix #8 Foliage with #2 Foliage to get #4 Foliage and #6 Foliage. Tube these four colors. Follow the formula exactly for the amount of paint indicated and you will arrive at the correct colors in the appropriate amounts.

|

| Another view of the mixing formula for foliage. |

Mixing the Sky Colors

Below, the chart for mixing sky colors. Create one tube for the sky zenith, an 8th value blue, and another tube for the sky horizon at 9.5 value blue green. In this iteration Reilly uses ultramarine blue and viridian, at other times he has mentioned thalo blue and green.

Another view of the mixing charts, this one including water. I have not found additional information to explain mixing colors for water .

Tubing the Paint

Below is a snapshot of my tubed summer colors. Empty tubes are available at Empty Paint Tubes - JerrysArtarama.com, utrechtart.com, and Pearl Paint 1.25oz Empty Aluminum Paint Tubes. They are available in various sizes from the 22ml that I used in the photo below, 45ml that I use for my fleshtones, and studio tubes. Choosing the size depends on how much you intend to use them.

To fill a tube with color, feed the paint into the open end with a narrow palette knife (or plastic butter knife) and tap the cap-end of the tube on your table to make the paint settle and remove the air. Once the tube is filled, crimp the open end shut with canvas pliers and fold it up.

|

22ml tubed landscape colors.

Also shown an empty 22ml tube and an empty 45 ml tube. |

The Shadows

Below Reilly compares the indoor palette and the outdoor palette. Outdoors all the shadows would be cool, ultramarine blue is a great color for adding to the shadows to affect the hue. On a sunny day, these values are never darker than 2, or lighter than 8.

The Lights

The lights can be influenced with cadmium yellow to make them warmer. These value range from 10 down to 5. Black in the light would be 5th value with a touch of cadmium yellow for warmth, and in the shadow painted at value 2 mixing lamp black and white. In the mini illustration, a white shape lays on the ground, painted a warm white at value 9 3/4, chroma 2. In the shadow it becomes a cool value 8, also at chroma 2.

Next Topic: Sky & Clouds